No Easy Answers

Sunday, December 31, 2006

Saddam's Last US Legal Action - Denied

Source: http://www.dcd.uscourts.gov/opinions/2006/2006MS566-21727-12292006b.pdf

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

IN RE SADDAM HUSSEIN Miscellaneous Action No. 06-566 (CKK)

MEMORANDUM OPINION

(December 29, 2006)

At approximately 1:00 p.m. today, Petitioner, Saddam Hussein, filed an Application for

Immediate, Temporary Stay of Execution with this Court. Petitioner's application asks that this

Court delay Hussein's sentence of death by an Iraqi court in order to protect his alleged due

process right to notice in a civil action presently before Judge Emmet G. Sullivan, Ali Rasheed v.

Hussein, Civ. A. No. 04-1862, in which Petitioner Hussein is named as a defendant. The Court

held two hearings in this matter during the late afternoon today, during which Petitioner's

counsel orally represented to the Court that he sought an order enjoining the United States

Military and the United States Department of State, under whose custody Petitioner Hussein

asserted he was allegedly being held, from transferring custody of Petitioner Hussein to the Iraqi

government for execution prior to January 4, 2007. Petitioner's counsel further represented that,

although his Application was not styled as such, he sought this order under the legal framework

of a petition for habeas corpus. Based on the pleadings and oral representations made by

Petitioner's counsel during the hearings before this Court, the Court shall deny Petitioner's

Application for Immediate, Temporary Stay of Execution.

I: BACKGROUND

As an initial matter, the Court notes that the Certificate of Service attached to Petitioner's

Application indicated that he served Secretary of Defense, Dr. Robert M. Gates, and Secretary of

State, Dr. Condoleezza Rice, by mail today. App. of Def. Saddam Hussein for Imm., Temp. Stay

of Execution (hereinafter "Pet.'s App."). The Court alerted Petitioner's counsel that this service

was inadequate because, pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4(i)(1), in addition to

serving Secretary Gates and Secretary Rice, Petitioner was required to effect service on the

United States Attorney for the District of Columbia and the Attorney General of the United

States. Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(i). Petitioner's counsel orally represented to the Court that he intended

to bring his Application pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(b), which allows a court

to grant a temporary restraining order without written or oral notice to the adverse party, pursuant

to certain conditions. Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(b). The Court determined, however, that Petitioner's

counsel had failed to meet the requirement of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(b)(2) because

counsel had not "certifie[d] to the court in writing the efforts, if any, which ha[d] been made to

give the notice and the reasons supporting the claim that notice should not be required." Fed. R.

Civ. P. 65(b)(2). Furthermore, the Court found that Petitioner's counsel, who indicated that he

discovered at 11:00 a.m. this morning that Petitioner Hussein was to be executed within the next

24-48 hours, had adequate time to serve the United States Attorney and the Attorney General, but

had failed to do so, or even to make efforts to reach or discuss his Application with government

counsel.

The Court held a hearing on the record in this matter during the late afternoon today,

during which Petitioner's counsel clarified certain matters. Without waiving service, and at the

2

request of the Court, Counsel from the Department of Justice, Federal Programs Division

participated by telephone. Based on Petitioner's counsel's assertion that Petitioner Hussein's

death sentence would be imposed within the next 24 to 48 hours, the Court determined that this

matter should be handled on an expedited basis, and as such, requested certain information from

the government, notwithstanding the fact that service had not been perfected. At the Court's

request, counsel for the government identified for the Court and Petitioner's counsel cases

relevant to the key jurisdictional issue in this matter, already identified by the Court whether

Petitioner Hussein was in the custody of the United States. At approximately 6:00 p.m. this

evening, the Court addressed an additional discrete question to Petitioner's counsel on the record,

at which point Petitioner's counsel also indicated that he had left service with the United States

Attorney's Office.

Petitioner's Application asserts that Petitioner has been named as a defendant in a civil

action, Ali Rasheed v. Hussein, Civ. A. No. 04-1862, currently pending before Judge Sullivan,

and that "his incarceration has prevented him from receiving proper due process notice of his

rights to defend himself and his estate" in that case. Pet.'s App. at 1. ^1 As a result, Petitioner's

Application requests that this Court delay Petitioner's sentence of death by the government of

Iraq, "to protect his right of due process and rights under the Geneva Conventions." Id. at 5.

Petitioner's Application cites Hill v. McDonough, 548 U.S. ___, 126 S. Ct. 2096, 2101, 165 L.

1

In an Order filed September 14, 2006, Judge Sullivan determined that Petitioner Hussein

had been properly served in Ali Rasheed v. Hussein pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure

4(f)(3) because service was effected upon his Counsel. Ali Rasheed v. Hussein, Civ. A. No. 04-

1862 (D.D.C. Sept. 14, 2006). The Court notes that Petitioner has subsequently filed a motion to

dismiss in Ali Rasheed v. Hussein, not fully briefed, in which he asserts that the court lacks

personal jurisdiction over him because he has not been properly served.

3

Ed. 2d 44, 51 (2006), a case arising under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, for the proposition that the Court

has the authority to order a stay of execution pursuant to its equitable powers. Id. Petitioner's

Application appends as exhibits two declarations one submitted by one of Petitioner Hussein's

criminal lawyers, the other by "Hussein's principal, Iraqi lawyer," Pet.'s App. at 1 which

indicate that, while Petitioner Hussein has been incarcerated in Iraq, these attorneys' access to

Petitioner Hussein has been at the discretion of the United States Military and Department of

State. Id. at 2. Based on these declarations, Petitioner Hussein asserts that he "is incarcerated

under the custody of the United States government through the United States military and the

Department of State." Id. at 1.

During the hearing on the record this afternoon, Petitioner's counsel clarified a number of

matters, including the following: (1) although Petitioner's Application asserted that this Court

had equitable powers to issue the remedy sought based on a case under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, he did

not seek to bring an action under that statute; (2) Petitioner's counsel represented that Petitioner,

in fact, sought a writ of habeas corpus; and (3) as to specific relief, Petitioner sought an order

enjoining the United States Military and Department of State from releasing Petitioner Hussein to

the custody of Iraqi officials for execution at any time prior to January 4, 2007, the date on which

Petitioner's counsel represented that Petitioner Hussein was scheduled to meet with attorneys

who would apprise him of the suit before Judge Sullivan.

III: DISCUSSION

"When it appears by suggestion of the parties or otherwise that the court lacks jurisdiction

of the subject matter, it shall dismiss the action." Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(h)(3). As such, "[i]f a court

determines that it lacks subject matter jurisdiction, it therefore is duty bound to dismiss the case

4

on its own motion." Hawk v. Olson, 326 U.S. 271, 272. 66 S. Ct. 116, 90 L. Ed. 61 (1945). The

following matters are not in dispute: (1) this Court, a court of limited jurisdiction, has no

jurisdiction over the Iraqi officials who will carry out the execution of an Iraqi citizen pursuant to

a sentence of death issued by an Iraqi court for violations of Iraqi law; (2) this Court only has

jurisdiction to issue a writ of habeas corpus if the petitioner is "in custody under or by color of

the authority of the United States," 28 U.S.C. § 2241; ^2 and (3) members of the United States

Military maintain custody over Petitioner Hussein pursuant to their authority as members of

Multi-National Force-Iraq ("MNF-I").

As Judge Reggie Walton recently concluded in a strikingly similar matter, this "Court

lacks habeas corpus jurisdiction over an Iraqi citizen, convicted by an Iraqi court for violations

of Iraqi law, who is held pursuant to that conviction by members of the Multi-National Force-

Iraq." Al-Bandar v. Bush, et al., Civ. A. No. 06-2209 (RMC) (D.D.C. Dec. 27, 2006) (denying

motion for temporary restraining order to prevent transfer of petitioner to Iraqi custody); see also,

Al-Bandar v. Bush, et al., Civ. A. No. 06-5425 (D.C. Cir. Dec. 29, 2006) (denying motion for

stay or injunction enjoining transfer of petitioner to Iraqi custody pending appeal). A United

States court has no "power or authority to review, affirm, set aside or annul the judgment and

sentence imposed" by the court of a sovereign nation pursuant to their laws. Hirota, et al. v.

General of the Army Douglas McArthur, et al., 338 U.S. 197, 198, 69 S. Ct. 197, 93 L. Ed. 1902

(1948); Flick v. Johnson, 174 F. 2d 983, 984 (D.C. Cir. 1949). Accordingly, this Court has no

2

Although Petitioner's counsel did not specify whether he brings the instant action under

statutory or constitutional habeas grounds, it is clear that the instant Petitioner cannot bring a

constitutional habeas action before the instant court. See Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U.S. 763,

768, 777-78, 70 S. Ct. 936, 94 L. Ed. 1255 (1950).

5

jurisdiction to prevent the transfer of Petitioner Hussein to the custody of the Iraqi government,

as that would effectively alter the judgment of an Iraqi court.

Moreover, Petitioner is not being held under the custody of the United States, and as a

result, this Court lacks habeas corpus jurisdiction. Petitioner's counsel agreed that, while

Petitioner may be held by members of the United States Military, it is pursuant to their authority

as members of the MNF-I. The MNF-I derives its "ultimate authority from the United Nations

and the MNF-I member nations acting jointly, not from the United States acting alone."

Mohammed v. Harvey, 456 F. Supp. 2d 115, 122 (D.D.C. 2006). As such, it is clear that

Petitioner is either in the actual physical custody of the MNF-I or in the constructive custody of

the Iraqi government, and not in the custody of the United States. Id. As Petitioner is clearly not

held in the custody of the United States, this Court is without jurisdiction to entertain his petition

for a writ of habeas corpus.

IV: CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, the Court shall DENY Petitioner's Application for

Immediate, Temporary Stay of Execution. An appropriate Order accompanies this Memorandum

Opinion.

Date: December 29, 2006

/s/

COLLEEN KOLLAR-KOTELLY

United States District Judge

6

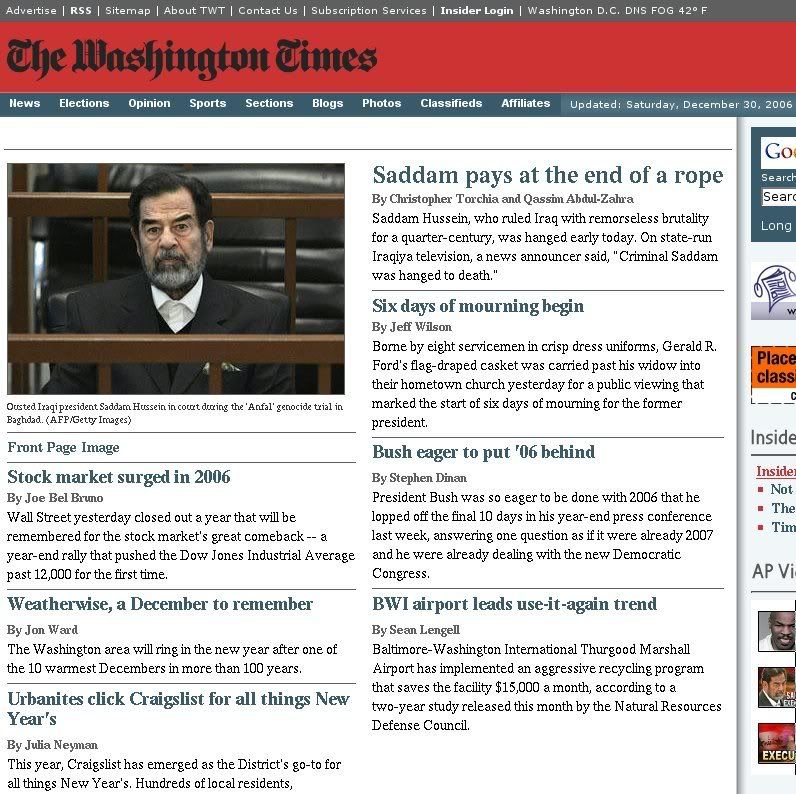

Saturday, December 30, 2006

A Most Unfortunate Juxtaposition

As presented by the Washington Times website:

Saddam pays at the end of a rope

By Christopher Torchia and Qassim Abdul-ZahraSaddam Hussein, who ruled Iraq with remorseless brutality for a quarter-century, was hanged early today. On state-run Iraqiya television, a news announcer said, "Criminal Saddam was hanged to death."

By Jeff WilsonBorne by eight servicemen in crisp dress uniforms, Gerald R. Ford's flag-draped casket was carried past his widow into their hometown church yesterday for a public viewing that marked the start of six days of mourning for the former president.

Preventing Identity Theft and Bending the Rules

Oh, and should you want to retrieve a piece of mail tendered to the USPS? Fuggedaboudit, it's against regulations, and perhaps against federal law. Once tendered to the USPS for delivery, mail is deemed out of the control of the sender. Usually.

Tax Forms Mailed With Soc. Sec. Numbers

Associated Press - December 30, 2006MILWAUKEE (AP) -- Wisconsin's revenue agency said Friday that it sent as many as 170,000 forms to taxpayers with mailing labels mistakenly printed with their Social Security numbers.

... "We want to prevent any chance identity theft might occur," department spokeswoman Meredith Helgerson said. An agency news release included an apology to taxpayers and a statement that steps were being taken "to make sure that this will never happen again."

The misprinted labels, blamed on a computer error while they were being prepared ...

... The agency said the postal service has agreed to retrieve and return any tax booklets that have not yet been delivered.

Dow Jones December 20, 2006 Motion to Unseal

Contrary to my first report posted hours ago, this motion ...

12/20/06 MOTION filed (Captioned MOTION of AMICI CURAIE DOW JONES

and the AP to UNSEAL)(5 copies) by Amicus Curiae for

Appellant Dow Jones Co Inc in 04-3138, Amicus Curiae for

Appellant Assoc Press in 04-3138 (certificate of service

dated 12/20/06 ) [1012356-1]

... was NOT filed under seal.

A small share of blame for reporting the presence of official secrecy might go to the Circuit Court clerks and the photocopy service for asserting that this motion was filed under seal. But given the nature of the filing, it is beyond ken that this filing would be under seal, and I have to take full responsibility for repeating via post that "the DJ Motion of December 20 was filed under seal." Additional research was certainly called for before piping up, and additional research resulted in finding that the filing was not under seal.

To the notion that this filing will produce something useful to the Libby trial, I have a one-word response. "Nonsense." The Court (with Fitzgerald's agreement) already released more than Dow Jones asked for in November, 2005 (Dow Jones didn't ask then for the release of affidavits, it asked only for release of redacted portions of the Opinion), and the Court released everything in the "Motion to Compel Reporter Testimony" that related to the prosecution of Libby. Any further releases are irrelevant to the question of whether or not Libby lied to investigators.

As to the notion that grand jury testimony relating to investigation of Rove should become public, based on Rove's admission, Armitage coming clean, and other public revelations to date, I assume the Court will reject the notion and the motion. The court and grand jury won't "lead" the publication of secret testimony, although they may well (and should) follow. Sure, we might see revelations such as "Karl Rove testified on such and so date," and technically, that constitutes the Court releasing more information. But I don't expect a release that documents why the Special Counsel was considering Rove as a target for a false statements and/or perjury charge, and I think that's what the bulk of the redactions comprise.

Transcribed by hand with only a spell check as a crutch. Blame me for typos, but pin your substantive criticism on Theodore J. Boutrous, Jr., Thomas H. Dupree, Jr. and Jack M. Weiss, all of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, LLP.

... ---oooOOO===OOOooo--- ...

MOTION OF AMICI CURIAE DOW JONES

AND THE ASSOCIATED PRESS TO UNSEAL

More than three years ago, the Deputy Attorney General of the United States appointed United States Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald to investigate the disclosure of the identity of CIA operative Valerie Plame. The principle questions at the time were whether the disclosure of Ms. Plame's identity was part of a concerted effort originating in the White House to discredit her husband, who was a critic of the President's war policies, and whether the disclosure violated federal criminal laws, including the Intelligence Identities Protection Act. As part of his investigation, the Special Counsel obtained orders compelling two reporters to disclose their conversations with confidential sources or be imprisoned; those orders ultimately led to one of the reporters being imprisoned for nearly three months.

Recently, the public learned that the Special Counsel's pursuit of those reporters was entirely unnecessary for him to determine who had leaked Ms. Plame's name to Robert Novak, the columnist who had first published it. The public now knows that the Special Counsel knew the identity of that leaker -- Richard Armitage, the former Deputy Secretary of State -- from the very beginning of his investigation.

This development regarding Mr. Armitage, along with recent public statements by the attorney for presidential advisor Karl Rove that the Special

Counsel has advised that Mr. Rove will not be charged in connection with this matter, justify releasing the remaining sealed portions of Judge Tatel's opinion in this case, as well as the Special Counsel's sealed affidavits. This will allow the public to gain a full understanding of the Special Counsel's arguments to the Court as to why it was necessary to compel the testimony of two reporters, and why it was necessary to imprison one of those journalists for 85 days for refusing to divulge her conversations with a different government official, I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby.

Accordingly, pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 27 and D.C. Circuit Rules 27 and 47.1, amici Dow Jones & Company, Inc. and the Associated Press respectfully move this Court to unseal all or some of the remaining redacted portions of Judge Tatel's opinion and the Special Counsel's sealed affidavits in this case. See In re Grand Jury Subpoena, Judith Miller, 438 F.3d 1138 (D.C. Cir. 2006)(ordering some, but not all, of these materials to be unsealed and stating that the Court would consider unsealing additional portions as the matter progressed). 1

--

1 Dow Jones and the Associated Press filed their

corporate disclosure statements in their amicus brief

submitted October 25, 2004.

2

BACKGROUND

This case arises from the disclosure of Valerie Plame's identity as a CIA operative. On February 15, 2005, a panel of this Court affirmed the district court's refusal to quash grand jury subpoenas issued to New York Times reporter Judith Miller, Time magazine reporter Matthew Cooper, and Time, Inc.

In so holding, the panel split three ways as to whether the common law and Federal Rule of Evidence 501 recognized a reporter's confidential source privilege. The panel agreed, however, that "if [a common law] privilege applies here, it has been overcome" by the Special Counsel's ex parte evidentiary proffer that purportedly established the need for the reporters' testimony and documents. 397 F.3d at 973. The panel stated that on this point it was adopting the reasoning of Judge Tatel's concurring opinion, which devoted eight pages to explaining how the Special Counsel, with his "voluminous classified filings," had "met his burden of demonstrating that the information [sought from reporters] is both critical and unobtainable from any other source." 397 F.3d at 1002 (Tatel, J., concurring). Those pages, however, which comprised eight pages of the slip opinion, were redacted from the versions of the opinion made available to the reporters and the public on the basis that they contained nonpublic grand jury information protected from disclosure pursuant to Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 6(e). 397 F.3d at 1002.

3

On November 2, 2005, in the wake of the grand jury's indictment of Mr. Libby, the former Chief of Staff to the Vice President of the United States, Dow Jones moved to unseal Judge Tatel's opinion in full or in part. On February 3, 2006, this Court granted the motion, unsealing certain portions of Judge Tatel's opinion, along with portions of one of the Special Counsel's affidavits that set forth his alleged need for reporters' testimony. See In re Grand Jury Subpoena, 438 F.3d 1138. The Court explained that "there is no longer any need to keep significant portions of the eight pages under seal," given that "Libby's indictment, now part of the public record, reveals some grand jury matters, and we see little purpose in protecting the secrecy of grand jury proceedings that are no longer secret." Id. at 1140. Thus, the Court "unseal[ed] those portions containing grand jury matters that the special counsel confirmed in the indictment or that have been widely reported." Id. The Court also unsealed "parts of one of the special counsel's affidavits upon which [it] relied in concluding that Miller's evidence was critical to the grand jury investigation," explaining that '[i]f the public is to see our reasoning, it should also see what informed that reasoning." Id.

The Court declined, however, to unseal the entirety of Judge Tatel's opinion or the Special Counsel's affidavits/ The Court noted that unsealing additional portions of these documents could identify witnesses or jeopardize the Special Counsel's ongoing investigation. Id. at 1141. But the Court recognized that

4

additional public disclosure could warrant unsealing the remaining portions of the opinion and affidavits, and thus emphasized that "[t]his order is without prejudice to Dow Jones's right to move to unseal additional materials at a later date." Id.

Subsequent to this Court's February 2006 ruling, two significant events have occurred that appear to warrant the unsealing of additional materials. First, former Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage has publicly disclosed that he was the source of the leak that led to the first public disclosure of the CIA affiliation of Valerie Plame. See Transcript of CBS Evening News at 3-4 (sept 7, 2006) (Attached as Exh. A); David Johnston, Source in C.I.A. Leak Case Voices Remorse, N.Y.Times (Sept. 8, 2006)(attached as Exh. B). Mr. Armitage has publicly stated that he told FBI investigators that he was the person who told columnist Robert Novak that Ms. Plame worked at the CIA, and that he also discussed Ms. Plame with Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward. Id. Mr. Armitage further stated that he disclosed his role in October 2003, but that Special Counsel "asked me not to discuss this and I honored his request." Exh A at 4; Exh. B at 2. He added that the Special Counsel has now given him permission to discuss these matters publicly. See Exh. B at 2 ("This week, after news reports clearly identified him as the source, Mr. Armitage said Mr. Fitzgerald had consented to his public disclosure of his role."); see also Robert Novak, My Role in the Plame Leak Probe, Chi. Sun-

5

Times (July 12, 2006)(discussing substance of his grand jury testimony)(attached as Exh. C); Robert Novak, The Real Story Behind the Armitage Story, Chi. Sun-Times (Sept. 14, 2006)(discussing conversation with Mr. Armitage)(attached as Exh. D).

Second, an attorney for presidential advisor Karl Rove has publicly disclosed that Mr. Rove was advised by the Special Counsel that he will not be charged in connection with this matter. See CNN.com, Lawyer: Rove won't be charged in CIA leak case (June 13, 2006)(attached as Exh. E)("White House senior advisor Karl Rove has been told by Special Counsel Patrick Fitzgerald that he will not be charged in the CIA leak case, according to Robert Luskin, Rove's lawyer."). Moreover, Matthew Cooper and Robert Novak have revealed their own testimony concerning Mr. Rove. See Matthew Cooper, What I Told the Grand Jury, Time, July 25, 2005, at 38; Novak, My Role in the Plame Leak Probe, Chi. Sun-Times (July 12, 2006).

ARGUMENT

As this Court has explained in its prior order in this case, "[g]rand jury secrecy is not unyielding," and thus "[j]udicial materials describing grand jury information must remain secret only 'to the extent and as long as necessary to prevent the unauthorized disclosure of a matter occurring before a grand jury.'" 438 F.3d at 1140 (quoting Fed. R. Crim. P. 6(c)(6))(emphasis added by the Court). The Court

6

noted that its precedent "reflects the common-sense proposition that secrecy is no longer 'necessary' when the contents of grand jury matters have become public" 438 F.3d at 1140. Indeed, "'[t]here must come a time . . . when information s sufficiently widely known that it has lost its character as Rule 6(e) material.'" Id. (quoting In re North, 16 F. 3d 1234, 1245 (D.C. Cir. 1994)). See also In re: Motions of Dow Jones & Co., 142 F.3d 496, 502 (D.C. Cir. 1998)(public disclosure of grand jury materials is warranted if doing so will not endanger grand jury secrecy, and "Rule 6(e)(5) contemplates that this shall be done")(emphasis added).

Here, the public statements of Mr. Armitage and Mr. Rove's lawyer strongly suggest that additional portions of Judge Tatel's concurrence and the Special Counsel's affidavits may now be unsealed. Where, as here, the witnesses themselves have made grand jury information widely known, continued secrecy is unwarranted. In In re: Motions of Dow Jones & Co., for example, the Court held that secrecy was in appropriate when a witness' attorney "virtually proclaimed from the rooftops that his client had been subpoenaed to testify before the grand jury." 142 F.3d at 505. The Court noted that the witness' "identity as a person subpoenaed to appear before the grand jury has become [public] information, not because of press reports relying on unnamed sources, but because [the witness'] attorney decided to reveal this fact to the public." Id.

7

In this case, Mr. Armitage has publicly revealed that he was the source of the leak that led to the first public disclosure of Ms. Plame's identity; that he told FBI investigators of this fact in October 2003, before the Special Counsel had even been appointed; and that Special Counsel asked him not to publicly discuss the matter, but recently released him from that promise. Likewise, Mr. Rove's lawyer has publicly revealed that Mr. Rove is not a target f the investigation and will not be charged in this case. These disclosures strongly suggest that additional portions of Judge Tatel's opinion and the Special Counsel's affidavits can be released without compromising the interests protected by Rule 6(e). See In re Grand Jury Subpoena, 438 F.3d at 1141 (declining to unseal additional material because "publication at this juncture could identify witnesses, reveal the substance of their testimony, and -- worse still -- damage the reputations of individuals who may never be charged with crimes"); id. (noting the need to protect information concerning witnesses' "role in the investigation"). Although the Court in its prior order noted that the fact that "the special counsel's investigation is ongoing only heightens the need for maintaining grand jury secrecy," id., it now appears that the Special Counsel's investigation is over.

These proceedings involve a matter of great public importance that has already received considerable publicity and public attention. In Washington Post v. Robinson, 935 F.2d 282 (D.C. Cir. 1991), this Court emphasized "the critical

8

importance of contemporaneous access . . . to the public's role as overseer of the criminal justice process." Id. at 287 (citing Richmond Newspapers, Inc. v. Virginia, 448 U.S. 555, 592 (1980)(Breman, J., concurring)).

These considerations carry special force here, where the criminal justice process has embroiled officials at the highest levels of the United States government and forced journalists to testify about their confidential sources. Unsealing the redacted portions of Jude Tatel's opinion and the Special Counsel's affidavits will enable the public to scrutinize the basis for this Court's ruling that any common law reporter's privilege was overcome. Furthermore, it will help the public understand the basis for the appointment of the Special Counsel and the Special Counsel's determination and argument that, notwithstanding Mr. Armitage's revelation in October 2003, he viewed it necessary to compel testimony from Ms. Miller and Mr. Cooper -- and force the imprisonment of Ms. Miller -- to fulfill his investigatory mandate.

9

CONCLUSION

For all the reasons set forth above, this Court should now unseal Judge Tatel's opinion and the Special Counsel's affidavits in their entirety or, at a minimum, unseal those portions that concern Mr. Armitage and Mr. Rove and that are no longer protected under Rule 6(e).

Dated: December 20, 2006

Respectfully Submitted,

Theodore J. Boutrous, Jr.

Thomas H. Dupree, Jr.

GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP

1050 Connecticut Avenue N.W.

Washington, D.C 20036

Jack M. Weiss

GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP

200 Park Avenue, 47th Floor

New York, NY 10166-0193

Attorneys for amici curiae

10

Friday, December 29, 2006

Fitzgerald's August 27, 2004 Affidavit

Source: http://online.wsj.com/public/resources/documents/libby-fitzgerald-affidavit-20060203.pdf

This affidavit was partially released on a favorable Circuit Court Ruling on Dow Jones's November 2, 2005 Motion.

Hat tip to yargb.blogspot.com for substantial portions of the text.

Pagination omitted. Footnotes are associated with their numbered points in the original, on a best-guess basis in cases where footnote numbers are themselves redacted from the publicly-released affidavit. Guesses of contents of redaction are noted in some places, likewise approximate length of some redactions.

Redactions conspicuous by absence:

- Mention of exhibits "M" and "N"

- Subheading Titles

- Testimony of government witnesses, inconsistent with Libby? (¶¶28-46)

- The factual background giving rise to the subpoenas issued to Cooper? (¶¶49-80)

In re: Grand Jury Subpoena, Miller

Cases Below (D.D.C.) 1:04-mc-00407, 1:04-mc-00408

Case on Appeal (D.C. Cir.) 04-3138

No. 04-3138

In re: Grand Jury Subpoena, Judith Miller

Consolidated with 04-3139, 04-3140

AUGUST 27, 2004 AFFIDAVIT OF PATRICK J. FITZGERALD

PLACED IN PUBLIC FILE PURSUANT

TO OPINION RELEASED FEBRUARY 3, 2006

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

...........................................

:

In re: Special Counsel Investigation : Case No. 04-MS-407 (D.D.C.)

: Case No. 04-MS-408 (D.D.C.)

(Grand Jury Subpoena to Judith Miller) : (Chief Judge Thomas F. Hogan)

:

REDACTED : UNDER SEAL

...........................................

PATRICK J. FITZGERALD, being duly sworn, deposes and says:Introduction

1. I am the United States Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois, having been appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate in October 2001. For purposes of the instant matter, I serve in the capacity as "Special Counsel," in that I have been delegated all the relevant powers vested in the Attorney General of the United States, including the power to issue subpoenas generally, to authorize subpoenas to the media and to appear in Court on behalf of the United States. I submit this affidavit in opposition to the Motions by (i) New York Times reporter Judith Miller [redacted (names movants to Motions to Quash, probably Cooper and Time, Inc.)] to quash grand jury subpoenas.

2. In this affidavit, I set forth below: the basis for my authority to conduct this investigation (paragraph 5); the general subject matter of the investigation (paragraphs 6 through 8); general factual background on the investigation (paragraphs 9 through 16); the factual background giving rise to the subpoenas issued to Miller (paragraphs 18 through 48); [redacted (probably parallels the previous - i.e., "the factual background giving rise to the subpoenas issued to Cooper")] the need for the reporters' testimony (paragraphs 81 through 83); the extent to which alternative remedies have been exhausted (paragraphs 84 through 88); and that the subpoenas were validly issued after a careful balancing of appropriate interests in free speech (paragraphs 89 through 100).

3. As discussed in greater detail below, reporter Miller has been subpoenaed because her testimony is essential to determine whether or not Lewis Libby, the Vice President's Chief of Staff, as committed crimes involving the improper disclosure of national defense information and perjury. Libby has admitted to speaking to reporter Miller in July 2003 and discussing the the purported employment of former Ambassador Joseph Wilson's wife by the Central Intelligence Agency ("CIA"). However, Libby has testified under oath that he only advised Miller that other reporters were saying that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA and that Libby himself did not know if that were true. There is substantial reason to question Libby's account. First, Libby testified that he merely relayed to Miller on July 12 or 13 what Libby had learned from Tim Russert on July 10. However, Russert has testified under oath that he did not discuss Wilson's wife with Libby on that date and indeed did not know then about Wilson's wife. Thus, Russert could not have then imparted that information to Libby. Moreover, Libby has given accounts of conversation with two other reporters [redacted] and Matt Cooper of Time magazine-- that are contradicted in many respects by the testimony of [redacted] and Cooper. And investigation to date has determined that Libby had spoken with as many as seven (7) different government officials about Wilson's wife [redacted] employment prior to the date of the Russert conversation when he claimed to have hear the information from Russert as if it were new. One of those officials, Ari Fleischer, was told the information by Libby three days before the purported Russert conversation and was advised by Libby that the information was "hush hush." The grand jury needs to hear the testimony of Miller before making any determination whether Libby should be charged. Libby has expressly waived any claim of confidentiality as to conversations with Miller on the subject matter of the investigation.

4. [redacted]

Authority to Conduct Investigation

5. In this particular matter, Attorney General John Ashcroft has recused himself from participation and delegated his full authority to Deputy Attorney General James B. Comey as Acting Attorney General The Deputy Attorney General is not recused from this matter but has delegated all the power he has concerning this matter to the letters dated December 30, 2003, and February 6, 2004, copies of which are annexed as Exhibits A and B. The Deputy Attorney General has exercised his discretion not to participate in the conduct of the investigation so as to allow him to participate fully in efforts to coordinate-national security matters with other members of the administration. Thus, as Special Counsel I serve as the functional equivalent of The Attorney General on this matter. 1

1 I have not been appointed pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Part 600, which is the provision allowing the Attorney General to appoint an attorney outside the Department of Justice to investigate and prosecute certain matters. In fact, the authority delegated in this case is in many respects broader than the authority conferred by the latter provision as I need not seek approvals prior to significant investigative or prosecutive steps.

The General Subject Matter of the Investigation

6. This investigation concerns the disclosure by government officials to the press in July 2003 of then classified information concerning the employment of Valerie Wilson Plame by the Central Intelligence Agency ("CIA"). In particular, the investigation seeks to determine which administration officials disseminated information concerning Ms. Plame to members of the media in spring 2003, the motive for the dissemination, and whether any violations of law were committed in the process. While the initial reporting regarding Ms. Plame's employment was in a column by syndicated columnist Robert Novak, 2 the investigation of unauthorized disclosures is not limited to disclosures to Novak. 3 Moreover, the investigation seeks to determine whether any witnesses interviewed to date have made false statements, committed perjury in the grand jury or otherwise obstructed justice.

2 Novak authored a Jury 14, 2003, Chicago Sun Times column revealing Plame's purported association with the CIA. (A copy of that column is annexed as Exhibit C.)

3 [redacted]

In seeking to determine the sources for these

disclosures, and the motives for the disclosures, the

investigation also necessarily has sought to determine whether,

as was reported in The Washington Post in September 2003,

administration officials called a number of other members of the

media in order to reveal information about Ms. Plame.

The investigation has focused primarily on

disclosures pre-dating July 14, 2003, the date of Novak's

column

7. In particular, this affidavit is submitted ex parte to apprise the Court why it is necessary that reporter Judith Miller of the New York Times be compelled to testify in compliance with a validly authorized grand jury subpoena as to conversations she had with I. Lewis Libby, a/k/a "Scooter Libby." Mr. Libby has signed a written waiver of confidentiality concerning his conversations with the media and upon information and belief has also expressly released at least cue other reporter (Matt Copper from Time) from any agreement of confidentiality.

8. [redacted] This affidavit is submitted under seal because it concerns a grand jury matter and is filed ex parte because it describes in detail various sensitive aspects of the grand jury investigation.

The Background Facts:

The Controversy About Niger and Uranium

9. The "leaks" under investigation must be viewed in the context of a controversy concerning the content of the State of the Union address delivered by President George W. Bush on January 28,2003. In that speech, President Bush stated: "The British government has learned that Saddam Hussein sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa." Those remarks, since referred to colloquially as the "16 words," were called into question by a series of articles in the spring of 2003, including several ultimately sourced in part to Ambassador Joseph Wilson. Wilson, a retired career State Department official who had been posted to a number of different African countries, had taken a trip to Niger at the request of the CIA in February 2002 to investigate allegations that yellowcake uranium had been sought or obtained by Iraq from Niger. (The CIA commissioned Wilson to take this trip after the CIA received inquiries from the Vice President about the allegation that uranium had been sought from Niger, but the Vice President himself did not request such a trip) Wilson reported to the CIA that he doubted the Iraq had obtained uranium from Niger recently, for a number of reasons. After the State of the Union speech, the International Atomic Energy Association revealed in March 2003 that documents apparently evidencing efforts to obtain yellowcake uranium from Niger were demonstrable forgeries. Thereafter, over the course of spring 2003, the "16 words" controversy attracted greater media attention. Wilson, who was not a government employee at the time of the trip and [about 65 characters redacted (probably a sentence break included, with the last words being "Richard Armitage")] spoke to several reporters, including Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times and Walter Pincus of the Washington Post, who wrote articles on May 6 and June 12 respectively concerning Wilson's trip to Niger, without naming Wilson. The articles called into question the accuracy of the "16 words." Those news stories generated significant conversation within and between the Office of the Vice President, the CIA, the State Department and the White House as to the circumstances under which Wilson's trip was undertaken.

The Wilson Op Ed Piece

10. On July 6, 2003, Wilson authored an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times entitled "What I Did Not Find in Africa" and was interviewed for an article in the Washington Post about his trip. Both items appeared in the July 6 editions of the respective newspapers. Also on July 6, Wilson appeared as a guest on Meet the Press, hosted that day by Andrea Mitchell. Those media appearances by Wilson generated heightened media interest and increased frustration in the Office of the Vice President that the Vice President was being identified incorrectly as the person sending Wilson on his trip. As a result of press inquiries at the White House the day following the articles and Wilson's television appearance, White House Press Secretary Ari Fleischer stated at a July 7, 2003 press "gaggle" that the Vice President had not requested Wilson's trip, had not been aware of it and had not been briefed on the results. [redacted]

11. Thereafter, the issue of how the "16 words" came to be in the State of the Union was a very prominent issue during the week of July 7 to July 12, while the President and several cabinet members were on a trip to Africa. The attention was increased in part by remarks by National Security Adviser Dr. Condoleeza Rice on Air Force One on July 10, 2003, which appeared to attribute blame for the "16 words" to the CIA. On Friday, July 11, 2003, CIA Director Tenet issued a written statement accepting responsibility for the inclusion of the "16 words" in the State of the Union address. [appears to be partially redacted]

12. [redacted]

4 As understood by various officials interviewed "on the record" comments are statements made for attribution to a government official by name. "Background" comments are comments that are attributed to a generic description of the government official. "Deep background" comments can be reported as part of the story but not specifically attributed to a government official. "Off the record" comments cannot be reported in the story but can be used to inform the reporter's understanding of the facts.

13. [redacted]

The Novak Column

14. On. Monday, July 14, 2003, Robert Novak published his syndicated column revealing that Wilson's wife was an "agency operative on weapons of mass destruction." Novak also reported, "[t]wo senior administration officials told me his [Wilson's] wife suggested sending Wilson to Niger to investigate the Italian report." A Time magazine piece authored by Mr. Cooper (as well as several coauthors) entitled "A War on Wilson?" appeared on the Internet later that week (July 17) which stated:

And some government officials have noted to Time in interviews (as well as to syndicated columnist Robert Novak) that Wilson's wife, Valerie Plame, is a CIA official who monitors the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. These officials have suggested that she was involved in her husband's being dispatched [] Niger to investigate reports...

(Copy annexed as Exhibit F.)

15. A Newsday article the following week quoted an intelligence official as confirming Valerie Plame's purported status' as a CIA employee. (Copy annexed as Exhibit D.)

16. The media published more information in the fall of 2003 confirming that Novak was not the only reporter contacted during the relevant period. The September 28, 2003, Washington Post reported that one unidentified source had advised that two top White House officials had contacted at least six reporters prior to the time that Novak published his July 14 story. (Copy annexed as Exhibit G.) The October 12 Washington Post story by Pincus and Allen revealed that a Washington Post reporter had been told about Wilson's wife's employment by an administration official on July 12, two days before Novak's column was published. (Exhibit E.) And Novak himself described the circumstances of his contact with his two administration sources in his October 1, 2003, Chicago Sun Times column. (Copy annexed as Exhibit H.)

The Instant Subpoenas

17. The instant subpoenas to New York Times reporter Miller concern conversations between I. Lewis Libby, a/k/a "Scooter Libby," and reporter Miller in July 2003 and related documents. Libby, a subject of this investigation who has testified twice before grand jury to date, is Assistant to the President, Chief of Staff to the Vice President, and Assistant to the Vice President for National Security Affairs. [redacted]

The Subpoena to Miller

Libby's Account of The July 8 Meeting Between Libby and Miller

18. Libby met with New York Times reporter Judith Miller on July 8, 2003. [redacted]

19. [redacted]

20. [redacted]

5 [redacted]

21. [5-6 lines redacted]

... Libby did not testify that Wilson's wife was discussed at the meeting - having repeatedly staked the position that he didn't discuss Wilson's wife with any one prior to July 10, the date when he thought he learned about Wilson's wife for the first time from Tim Russert. As discussed elsewhere, however, there appears to have been no such conversation with Russert about Wilson's wife on July 10 and Libby was discussing Wilson's wife with others prior to July 10. Thus, it is plausible that Libby may have discussed with Miller Wilson's wife on July 8, given that he discussed Wilson's wife with Ari Fleischer on July 7 and he admits discussing Wilson's wife with Miller at least on July 12.

Libby's Account of The July 12 Telephone Call Between Libby and Miller

22. Libby testified that he spoke to Judith Miller on July 12 or Jury 13 about Wilson's wife by telephone from his home, believing that the call occurred on Jury 12. The call to Miller would have followed conversations described below with reporters Matt Cooper (Time magazine)

[paragraphs redacted]

Libby's Claimed Basis for Knowledge About Wilson's Wife

23. Libby testified in the grand jury that Tim Russert of NBC advised him by telephone on or about July 10 or July 11, 2003, that Wilson's wife worked for the CIA. Libby testified that he believed he was learning this information for the first tone from Russert. Libby further testified that he thereafter spoke to reporters [redacted (reporter name(s))(Glenn Kessler of the Washington Post)] Matt Cooper of Time magazine and Judith Miller of the New York Times and discussed with them the fact that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA, relaying what he heard from Russert (and what Karl Rove also told him that Rove had learned from Robert Novak). Libby acknowledged that his own notes indicated that he had been advised by the Vice President in early June 2003 that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA. Libby maintained, however, that while he had learned that fact from the Vice President in June, he had forgotten about it by the time he spoke to Russert in early Jury. Further, according to Libby, he did not recall his conversion with the Vice President even when Russert allegedly told him about Wilson's wife's employment.

[redacted (one line)] ... Because Libby's account is substantially at odds with essentially every material witness questioned to date, Libby's account is set forth in detail below and compared with the accounts of other witnesses.

Libby's Account of His July 10 Conversation With Tim Russert

24. More specifically, Libby has testified that he spoke with Tim Russert on July 10 or 11, 2003, when Libby called to complain to Russert in Russert's capacity as NBC Washington Bureau chief about what Libby perceived to be unfair coverage by Chris Matthews of MSNBC. (Matthews was reporting that the Vice President and/or his staff knew about Wilson's trip to Niger and thus, in Matthews' view, knowingly allowed the President to mislead the public in the State, of the Union.) During that conversation, Libby claims that Russert advised Libby that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA and that "all" the reporters knew that information. As noted above, Libby specifically recalls believing that he was learning that fact for the first time even though by his own admission Libby's notes show that he had been told this fact by the Vice President the month before. (Exhibit I at pages 84-87.) When confronted on whether he had discussed Wilson's wife with other government officials earlier that week -- including White House press secretary Ari Fleischer, Director of Communications for the Vice President Cathie Martin and others -- Libby's repeated refrain was that he could not have discussed the matter earlier in the week because he specifically recalled that he learned about Wilson's wife from Russert that week as if it were new (Exh. L at 156-60).

25. Libby explained in detail how he was certain he said nothing to confirm what Russert said was true and that in fact that he did not recall what he knew about Wilson and his wife at the tune of the conversation:

[Russert asked] "did you know that Wilson's wife works at the CIA?" taken aback by that I remember being taken aback by it And I said -- he may have said a little more but that was -- he said that. And I said, no, I don't know what intentionally because I didn't want him to take anything I was saying as in any way confirming what he said because at that point in time I did not recall that I had ever known and I though that this was something that he was telling me that I was first learning. And so I said, no, I don't know that because I want to be very careful not to confirm it for him so that he didn't take my statement as confirmation for him.. . . [Libby then clarifies mat he had made clear that the Russert conversation had been off theme record]

So then he said - I said -- he said, sorry -- he, Mr. Russert said to me, did you know that Ambassador Wilson's wife, or his wife, works at the CIA? And I said, no, I don't know that. And then he said, yeah -- yes, all of the reporters know it. And I said again, I don't know that ... I just wanted to be clear that I wasn't confirming anything for him on this. And you know, I was struck by what he was saying in that he thought it was important fact, but I didn't ask him any more about it because I didn't want to be digging in on him and then he moved on and finished the conversation...

(Exh. I at 143)

Russert's Account of His Conversation With Libby

26. Russert testified under oath that he had no recollection that he and Libby discussed Wilson's wife during that week. Russert recalled neither being advised by Libby that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA nor advising Libby of the same. Russert recalled that Libby did call to complain to him about Chris Matthews coverage. Russert recalled that when he first read Novak's column on July 14, 2003, that he had a reaction of "wow" because reading the article was the first time he had heard of Wilson's wife's purported affiliation with the CIA. (Transcript of Russert's Deposition annexed as Exhibit K). In addition, Russert had not heard any reporters talking about Wilson's wife working at the CIA before the Novak column appeared. Having not heard that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA, and not having heard that any reporters were saying that prior to Novak's July 14 column, it thus appears impossible that Russert advised Libby on July 10 or 11 that "all" the reporters were saying Wilson's wife worked at the CIA. Indeed, Russert advised that had he known that Wilson's wife was purported to be a CIA employee prior to reading Novak's column, he would have taken steps to have NBC investigate that story, which he had no recollection of doing.

Other Information Inconsistent with Libby's Account

27. Moreover the record developed in the course of this investigation suggestions that as many as seven government officials discussed Wilson's wife's employment at the CIA with Libby prior to the date when Libby claims to have learned this information (for what he claims to have then believed was the first time) from Russert:

(1) As indicated above, Libby now admits being told by the Vice President about Wilson's wife's employment in early June 2003; 6

(2) Undersecretary of State Marc Grossman recalls telling Libby in early June 2003 that "Joe Wilson's wife works for the CIA" and that "our people say that she was involved hi the organization of the-trip."

(3) [redacted] a former member of the communications staff for the Office of Vice President, recalls advising Libby [redacted] in June or early July 2003 (at a time that appears to be prior to the date of the purported Russert conversation) that she had heard that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA.

(4) David Addington, Counsel for the Office of the Vice President, recalls being asked privately by Libby in the week of July 7 what kind of paperwork the CIA would maintain if an employee's spouse were sent on a trip by the CIA. Addington testified that from the context of the question he understood Libby to be discussing Wilson and Wilson's trip to Niger.

(5) A CIA employee assigned to provide daily intelligence briefs to the Vice President and Libby has handwritten notes indicating that Libby referred to "Joe Wilson" and "Valerie Wilson" by those names in conversation with the briefer on June 14, 2003 - a month before the Russert conversation.

(6) [5 lines redacted] After a June 2003 article about Iraq and the uranium issues that caused concern to Edelman and Libby, Edelman asked Libby whether information about how the Wilson trip came about could be shared with the press to rebut allegations that the Vice president seat Wilson. Edelman testified that Libby responded by indicating that there would be 'complications" at the CIA in disclosing that information publicly. Ambassador Edelman indicated that he understand that he and Libby could not further discuss the matter because they were speaking on an open telephone line and Edelman understood that this might involve classified information

(7) Former White House press secretary Ari Fleischer, [redacted (maybe additional names)] testified that he went to lunch with Libby on Monday, July7, 2003, and in a conversation Fleischer described as "weird," Libby told Fleischer that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA. Libby told Fleischer the information about Wilson's wife was "hush hush" or "on the QT." Thus, according to Fleischer, Libby imparted what Libby appeared to have considered sensitive information about Wilson's wife's employment three days prior to when he claims to have received it as "new" information during the Russert conversation.

6 [redacted]

7 [redacted]

28. [redacted]

29. [redacted]

30. [redacted]

31. [redacted]

32. [redacted]

8 [redacted]

33. Libby testified that Cooper then asked why Wilson was claiming that the Vice President had sent him to Niger if the Vice President had not. Libby testified that he then explained to Cooper that Wilson might have heard something unofficial (and inaccurate) about the Vice President sending Wilson and "in that context" and "off the record" Libby told Cooper that "reporters are telling us" that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA "and I don't know if it's true" (Exh. I at 182-86). Libby testified several times that he told Cooper (and the other relevant reporters discussed below, including Miller) that he did not know if the information was true or even if Wilson had a wife. 9

9 "And when I talked to the reporters about it, I explicitly said, you know, I don't know if this is true, I don't know the man, I don't know if he has a wife, but reporters are telling us that." (Exhibit J at 177.)

"And you're certain as you sit here today that

every reporter you told that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA, you

sourced it back to other reporters?"

A: "Yes, sir ..."

(Exhibit J at 181.)

34. [redacted]

35. [redacted]

10 [redacted]

11 [redacted]

36. [redacted]

37. [redacted]

38. [redacted]

39. [redacted]

40. [redacted]

41. [redacted]

12 [redacted]

42. [redacted]

43. [redacted]

13 [redacted]

44. [redacted]

45. [redacted]

46. [redacted]

[redacted] Paragraph one of the subpoena requested documents concerning conversations between July 6 and July 13 between Judith Miller and a "government official with whom she met in Washington. D.C., on July 8,2003, concerning Valerie Plame... or concerning Iraqi efforts to obtain uranium."

[redacted]

Libby's Waiver of Confidentiality

47. To the extent that a "reporter's privilege" is claimed to exist under the law, Libby has waived its protections. Libby has executed a signed waiver which recites in pertinent part:

I have informed the Federal Bureau of Investigation of my recollection of any communications I have had with members of the media regarding the subject matters under investigation. I hereby waive any promise of confidentiality, express or implied, made to me by any member of the media in connection with any communications that I may have had with that member of the media regarding the subject matters under investigation, including any communications made "on background," "off the record," "not for attribution," or in any other form. I request any member of the media with whom I may have communicated to fully disclose all such communications to federal law enforcement authorities. In particular, I request that no member of the media assert any privilege or refuse to answer any questions from federal law enforcement authorities on my behalf or for my benefit in connection with the subject matters under investigation.

(Exh. L)

48. Libby has also described his version of his conversations with reporter Miller under oath before the grand jury on two occasions. And, as discussed above, Libby has apparently provided express consent (through his lawyer) for Cooper to testify. Cooper testified at his deposition that he agreed to testify because he was convinced based upon his attorney's conversation with Libby's attorney that Libby voluntarily released Libby from any promise of confidentiality. Thus, to the extent that Judith Miller calls into question the voluntariness of Libby's waiver, she need look no further than to her own attorney (who represents Cooper as well) who, according to Cooper, has assessed that Libby's waiver of confidentiality has been voluntary.

49. [redacted]

50. [redacted]

51. [redacted]

52. [redacted]

53. [redacted]

54. [redacted]

55. [redacted]

56. [redacted]

57. [redacted]

14 [redacted]

58. [redacted]

59. [redacted]

60. [redacted]

61. [redacted]

62. [redacted]

63. [redacted]

64. [redacted]

65. [redacted]

66. [redacted]

67. [redacted]

68. [redacted]

69. [redacted]

70. [redacted]

71. [redacted]

72. [redacted]

73. [redacted]

74. [redacted]

75. [redacted]

76. [redacted]

77. [redacted]

78. [redacted]

79. [redacted]

80. [redacted]

The Need for the Reporters' Testimony

81. The testimony of reporter Miller is central to the resolution of that part of the criminal investigation concerning Libby. Her testimony is essential to determining whether Libby is guilty of crimes, including perjury, false statements and the improper disclosure of national defense information. 15 The grand jury needs to know when Libby advised Miller about Wilson's wife -- during their private meeting outside the White House on July 8 or during the three minute telephone call on July 12 -- and whether Libby qualified his disclosure to Miller by stating that he had heard it only from a reporter and did not know if it were true. Miller's testimony is essential to determine whether Libby fabricated his claim that he only told reporters what he claimed he had heard from Russert without a belief that the information he was passing on was either true or classified.

15 If Libby knowingly disclosed information about Plame's status with the CIA, Libby would appear to have violated Title 18, United States Code, Section 793 if the information is considered "information respecting national defense." In order to establish a violation of Title 50, United States Code 421, it would be necessary to establish that Libby knew or believed that Plame was a person whose identity the CIA was making specific efforts to conceal and who has carried out covert work overseas within the last 5 years. To date, we have no direct evidence that Libby knew or believed that Wilson's wife was engaged in covert work.

82. [5 lines redacted]

Miller would shed light on the context in which any conversation about Wilson's wife took place.

83. [redacted]

Exhaustion of Alternative Remedies

84. All reasonable alternatives to compelling the reporters' testimony have been explored. Indeed, the effort expended to date far exceeds what could ever be reasonably required. An experienced team of FBI agents has been working on the case since October 2003, led by Special Agent Jack Eckenrode then of the Inspection Division. At least six agents have been assigned to the case at any time and extensive forensic computer and telephone work is being done. Attorneys with the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice: a Deputy Assistant Attorney General; the Chief Deputy Chief and a Trial Attorney from the Counterespionage Section; and a Trial Attorney from the Public Integrity Section. All five attorneys are well versed in the facts and participating to varying degrees in interviews of witnesses, review of documents and examination of witnesses before the grand jury. From the United States Attorney's Office in Illinois, a number of senior attorneys have participated. Besides my own participation in the factual investigation, the First Assistant United States Attorney, the Chief of the Criminal Division, the Chief of Appeals and the Chief of Public Corruption have participated to varying degrees in the discussion of legal issues, including analyzing the relevant statutes, analyzing the First Amendment issues and determining the available means to obtain electronic evidence. An additional attorney from the appellate section has spent substantial time on legal research and briefing in recent months.

85. The Department of Justice has been investigating this matter since about October 1, 2003, and my participation as Special Counsel began in late December 2003. [4-5 lines redacted]

86. [redacted]

87. [redacted]

88. In short, wherever the line should be drawn in requiring the government to explore alternative remedies, we respectfully submit that any reasonable threshold that might be set has been far exceeded.

The Subpoenas Are Issued Legitimately and Not For Purposes to Harass

89. It is important to bear in mind that the applicable regulations do not "create any legally enforcible right in any person" (See Title 28 Code of Federal Regulations, Section 50.10, a copy of which is annexed as Exhibit O, at paragraph (n)). Nonetheless, issuance of the subpoena at issue was consistent with the principles set forth in those regulations. First, the subpoenas are narrowly drafted after a careful balancing of the First Amendment interests. Indeed, as set forth in the next section, a number of reporters, and their toll records, are not being subpoenaed at this time. Most will likely never be subpoenaed.

90. [redacted]

91. [redacted]

92. Subpoenas were issued to Matt Cooper and Time magazine, as well as Tim Russert and NBC. After motions to quash the subpoenas were denied, Russert and NBC agreed to a deposition. After Cooper and Time were held in contempt, but prior to appeal, they agreed to a deposition.

[6-7 lines redacted]

93. [redacted]

16 [redacted]

94. In deciding whether to issue subpoenas to reporters, I have carefully weighed and balanced the competing interests of the First Amendment and the public interest in the free dissemination of ideas and information and the countervailing interests in effective law enforcement and the fair administration of justice; namely determining whether a crime was committed and whether someone should be prosecuted for that crime. One key factor in deciding whether to issue a subpoena has been whether the "source" to be identified appears to have leaked to discredit the early source (Wilson) as opposed to a leak who revealed information as a "whistleblower" (e.g., the source for the September 28 Washington Post column). The First Amendment interests are clearly different when the "source" being sought may have committed a crime in order to attack a person such as Wilson who, correctly or incorrectly, sought to expose what he perceived as misconduct by the White House. Indeed, failure to effective steps to identify such sources might chill future whistleblowers such as Wilson, thus impairing "a reporter's responsibility to cover as broadly as possible controversial public issues." (28 CFR Section 50.1). We have also not issued subpoenas to date where the reporter may have relevant information but it is shown to be likely that the reporter does [phrase redacted] or where the information is not essential to determining guilt or innocence of a crime likely to be charged.

95. [redacted]

96. The instant subpoenas were issued only after first making certain that any efforts at a negotiated resolution would be fruitless. Indeed, Special Counsel has engaged in fruitful negotiations with other members of the media.

97. There are reasonable grounds to believe based on information from nonmedia sources that a crime has occurred -- both the improper disclosure of national defense information to the media and perjury before the grand jury -- and that the testimony of reporters Miller [name redacted (and Cooper?)] is essential to a successful investigation and may directly establish Libby's guilt or innocence, and [1-2 lines redacted (that the testimony of reporter Cooper may directly establish Rove's guilt or innocence?)]. The subpoenas are not issued to obtain peripheral, nonessential or speculative information.

98. There are no alternative nonmedia sources to provide accounts of what Libby told Miller -- all others, including Libby, have been questioned extensively. [short sentence redacted] And the subpoenas are issued to verify published information and surrounding circumstances relating to the accuracy of the published information, including information published in the Washington Post that "top White House officials" were contacting reporters prior to July 14, 2003, and more specific information published in the Washington Post that one of its reporters was told about Wilson's wife on July 12, 2003. And the subpoenas are directed at material information regarding a limited subject matter. Miller's subpoena focuses on particular conversations with a single person (Libby) on given dates. [3-4 lines redacted]

99. Indeed, on the facts of this case, it is hard to imagine a stronger case: Libby claims that he told Miller only what he heard "reporters are telling us." Thus, we are in the remarkable position of having identified the person who spoke to Miller and having obtained that person's consent to having Miller disclose the conversation. To deprive the grand jury of the ability to hear and assess Miller's account of what Libby told her is to ask the Special Counsel and the grand jury to make a decision on prosecution partly in the blind -- where it is unknown whether the information will be inculpatory or exculpatory. The possible consequences of a mistake -- wither the failure to charge what would otherwise be determined to involve a crime carried out to discredit a source who was a whistleblower or, worse, charging a confidential source in good faith with a crime where the claim of a "reporter's privilege" deprived the investigation of exculpatory information -- could do far more to undermine both First Amendment interests and the fair administration of justice that could enforcement of the subpoenas. Indeed, the testimony of reporter Cooper was distinctly different from what Libby testified [phrase redacted]. Given that Libby's account of conversations has been largely inconsistent with every other material witness to date [phrase redacted] the only way to make an appropriate decision as to whether Libby committed a crime in his conversation with Ms. Miller -- or in his sworn testimony describing the same -- is to question Miller.

100. [redacted]

Dow Jones Motion to Unseal - November 2, 2005

CADC Case No. 04-3138

One of the Motions of Dow Jones, to unseal the Opinion and Affidavits of the prosecutor in the cases In re: Grand Jury Subpoenas, Judith Miller et al, is a matter of public record.

11/2/05 MOTION filed (5 copies) by Amicus Curiae Dow Jones & Co.,

Inc. in Nos. 04-3138, 04-3139, 04-3140 (certificate of mail

service date 11/2/05) to unseal [929790-1].

The text of the above-noted November 2, 2005 motion is reproduced below, as a hand transcription. It was followed, of course, by a Government Response & Resulting Court Opinion.

In contrast to the November 2, 2005 Motion being a "matter of public record," last year's Reply by movant Dow Jones, and the recent (December 20, 2006) Motion to Unseal ...

12/6/05 REPLY filed [935817-1] (5 copies) by Amicus Curiae Dow

Jones Co Inc, et al. (certificate of service dated 12/6/05)

to a response to the motion unseal. [929790-1]

12/20/06 MOTION filed (Captioned MOTION of AMICI CURAIE DOW JONES

and the AP to UNSEAL)(5 copies) by Amicus Curiae for

Appellant Dow Jones Co Inc in 04-3138, Amicus Curiae for

Appellant Assoc Press in 04-3138 (certificate of service

dated 12/20/06 ) [1012356-1]

... are themselves SEALED at the Circuit Court of Appeals, according to

the document retrieval and copying service authorized by the United States Circuit Court

of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

If that is had been in fact true, I find more than a hint of irony that a

Motion to Unseal is itself sealed, where the movant is asking for relief on the grounds of

making more information available to the public. The movants (Dow Jones and Associated Press),

who could make the material public, aren't making the material public.

That suggests that Dow Jones' current (December 2006) motion contains information pertinent to subpoenas to Miller, Cooper and Time other than what is relevant in the Libby case, and the Court, in an exercise of prudent judgment, is unwilling to be used as a publication tool for Dow Jones.

FLASH!! FLASH!!

The clerk of the court and the document retrieval service were in error. The December 20, 2006 Motion to Unseal is emphatically NOT filed under seal.

December 20, 2006 Motion to Unseal

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

IN RE GRAND JURY SUBPOENAS TO JUDITH MILLER

IN RE GRAND JURY SUBPOENAS TO MATTHEW COOPER

IN RE GRAND JURY SUBPOENA TO TIME INC.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For the District Of Columbia

MOTION OF AMICUS CURIAE DOW JONES TO UNSEAL

Theodore J. Boutrous, Jr.

Thomas H. Dupree, Jr.

GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP

1050 Connecticut Avenue N.W.

Washington, D.C 20036

Jack M. Weiss

GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP

200 Park Avenue, 47th Floor

New York, NY 10166-0193

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

MOTION OF AMICUS CURIAE DOW JONES TO UNSEAL

Pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 27 and D.C. Circuit Rules 27 and 47.1, amicus Dow Jones & Company, Inc. respectfully moves this Court to unseal the redacted portions of Judge Tatel's opinion in this case. See 397 F.3d 964, 1002; slip op. at 30-39 (attached as Exhibit A). 1

INTRODUCTION

This case arises from the disclosure of Valerie Plame's identity as a CIA operative. On February 15, 2005, a panel of this Court affirmed the district court's refusal to quash grand jury subpoenas issued to New York Times reporter Judith Miller, Time magazine reporter Matthew Cooper, and Time, Inc.

In so holding, the panel split three ways as to whether the common law and Federal Rule of Evidence 501 recognized a reporter's confidential source privilege. The panel agreed, however, that "if [a common law] privilege applies here, it has been overcome" by the Special Counsel's ex parte evidentiary proffer that purportedly established the need for the reporters' testimony and documents. 397 F.3d at 973; slip op. at 17. The panel stated that on this point it was adopting the reasoning of Judge Tatel's concurring opinion, which devoted eight pages to

--

1 Dow Jones filed its corporate disclosure statement

in its amicus brief submitted October 25, 2004.

explaining how the Special Counsel, with his "voluminous classified filings," had "met his burden of demonstrating that the information [sought from reporters] is both critical and unobtainable from any other source." 397 F.3d at 1002 (Tatel, J., concurring); slip op. at 30. Those pages, however, were redacted from the versions of the opinion made available to the reporters and the public on the basis that they contained nonpublic grand jury information protected from disclosure pursuant to Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 6(e). 397 F.3d at 1002; slip op. at 30-39.

On October 28, 2005, the grand jury indicted I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby, the then-Chief of Staff to the Vice President of the United States, on charges arising out of the Special Counsel's investigation. The indictment, attached hereto as Exhibit B, describes conversations Mr. Libby allegedly had with Ms, Miller and Mr. Cooper as forming the factual basis for certain charges. Shortly after the release of the indictment, the Special Counsel held a press conference in which he discussed the indictment and his investigation in more detail. A transcript of the press conference is attached hereto as Exhibit C.

As shown below, this Court should now unseal the redacted pages of Judge Tatel's opinion in their entirety or, at a minimum, unseal those portions that are no longer protected under Rule 6(e) in light of the indictment, the Special Counsel's public statements, and the public statements of the witnesses themselves.

2

ARGUMENT

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 6(e)(6) provides that orders relating to grand jury proceedings must be kept under seal only "to the extent and as long as necessary" to prevent the unauthorized disclosure of grand jury matters. See also D.C. Circuit Rule 47.1(c)("[a] party or any other interested person may move at any time to unseal any portion of the record in this court"); D.D.C. Local Rule 6.1 (district court may make public sealed documents concerning grand jury proceedings if the court determines "that continued secrecy is not necessary to prevent disclosure of matters occurring before the grand jury").

In In re: Motions of Dow Jones & Co., 142 F.3d 496 (D.C. Cir. 1998), this Court held that although there is no First Amendment right of access to judicial records and proceedings ancillary to the grand jury, public disclosure of such materials is warranted if doing so will not endanger grand jury secrecy. Indeed, "Rule 6(e)(5) contemplates that this shall be done." 142 F. 3d at 502 (emphasis added). The Court explained that while "[i]t is true that Rule 6(e) does not create a type of secrecy which is waived once public disclosure occurs . . . it is also true that when information is sufficiently widely known . . . it has lost its character as Rule 6(e) material." Id. at 505 (internal quotations and citations omitted).

Accordingly, this Court has directed that its opinions be unsealed when their content no longer qualifies as Rule 6(e) material. See, e.g., In re Lindsey, 158 F.3d

3

1263, 1265-66 (D.C.Cir. 1998)(ordering "that the redacted portions of this Court's opinion . . . are no longer protected from public disclosure by Rule 6(e)" and that "the entire opinion of this Court . . . shall be unsealed"); In re: Sealed Case, 162 F.3d 670, 671-72 (D.C.Cir. 1998)(unsealing opinion of the Court).

Here, the grand jury's indictment and the Special Counsel's public statements strongly suggest that the redacted portions of Judge Tatel's opinion are no longer protected from public disclosure by Rule 6(e). Among other things, the indictment discloses conversations Mr. Libby allegedly had with Ms. Miller and Mr. Cooper. Exh B. at p6, ¶14; p7, ¶17; p8, ¶¶22-24. The indictment also discloses Mr. Libby's statements to the FBI concerning those conversations, id. at p9, ¶26; p17, ¶¶2-3, as well as his (and apparently the reporters') grand jury testimony about the conversations. Id. at pp11-14, ¶¶32-33; pp20-22, ¶¶2-3. Indeed, the indictment includes lengthy verbatim quotations from Mr. Libby's grand jury testimony concerning his conversation with Mr,. Cooper. Id. at p20, ¶2.

More generally, the indictment discloses the nature and "major focus" of the grand jury's investigation, as well as the various matters that were material in the investigation, including "[w]hether and when LIBBY disclosed to members of the media that [Plame] was employed by the CIA." Id at pp9-10, ¶¶27-29.

Similarly, in his press conference following issuance of the indictment, the Special Counsel disclosed that "Mr. Libby was the first official known to have told

4

a reporter when he talked to Judith Miller in June of 2003 about Valerie [Plame]." Exh. C at 1. See also id. at 3-5 (discussing Mr. Libby's conversations with Ms,. Miller and Mr. Cooper and stating that "It's important to focus on what it is that Mr. Libby said to the reporters"); id. at 10-11, 25 (discussing need for reporters' testimony). Indeed, the Special Counsel explicitly recognized that while "this grand jury investigation has been conducted in secret . . . [w]e are now going from a grand jury investigation to an indictment, a public charge and a public trial. The rules will be different." Id. at 5.